The first thing Stevie Wonder said to me that day was, “Show me the pictures.” I played along.

“Right here,” I said. We sat side by side, legs dangling over the edge of the stage in a cavernous rehearsal hall. I set my portfolio on his lap and opened it for him.

“Oh wow, man! These are cool,” said he, flipping pages and feigning an over-the-top Braille that looked like playing arpeggios on a concert grand piano. Then he said, with arch seriousness, “You’re getting better.”

“I love your work, too, Steve,” I replied. “But I don’t rub my ears all over your records. You’re ruining my prints.” I got a hug.

It wasn’t the first time we’d met; I’d photographed Steve a number of times. Incidentally, at any rung on the ladder of propinquity, people called him Steve; Stevland Morris Hardaway officially — with only one e. This time Motown’s Tamla record label hired me for a photoshoot to publicize his professional comeback from a near-death experience.

It happened in the summer of 1973. Steve and his band were on a road trip to promote their new album, Innervisions. After a performance in Greenville, South Carolina, they were headed to Durham, North Carolina, to visit America’s first community-owned black radio station, WAFR. They didn’t make it. Leading a three-car caravan up the Interstate, with Steve riding shotgun and his cousin at the wheel, they rear-ended a flatbed farm truck in broad daylight. There is no consensus to explain how that happened in the first place. But there is no ambiguity about how the grille of their car plunged underneath the extended lip of the truck bed, which, like a chisel, tore across the hood and broke through the windshield, striking Steve in the head before the truck itself was flung headlights over hubcaps off the highway.

Pulling up to the scene, the panicked sidemen couldn’t wait for a random cop passing by to radio for an ambulance. They rushed Steve, bleeding and unresponsive, to the closest hospital. He was stabilized and transferred to intensive care in Winston-Salem where he lay disfigured and in a coma for four days. Steve’s cousin suffered minor lacerations; the truck driver broke both of his ankles. In the weeks that followed, Steve was moved to the UCLA Medical Center in West LA, where family, friends, and fans endured his anxious convalescence. Steve was personally tormented by the possibility of losing his musical faculties. Thank goodness, we all know the upshot.

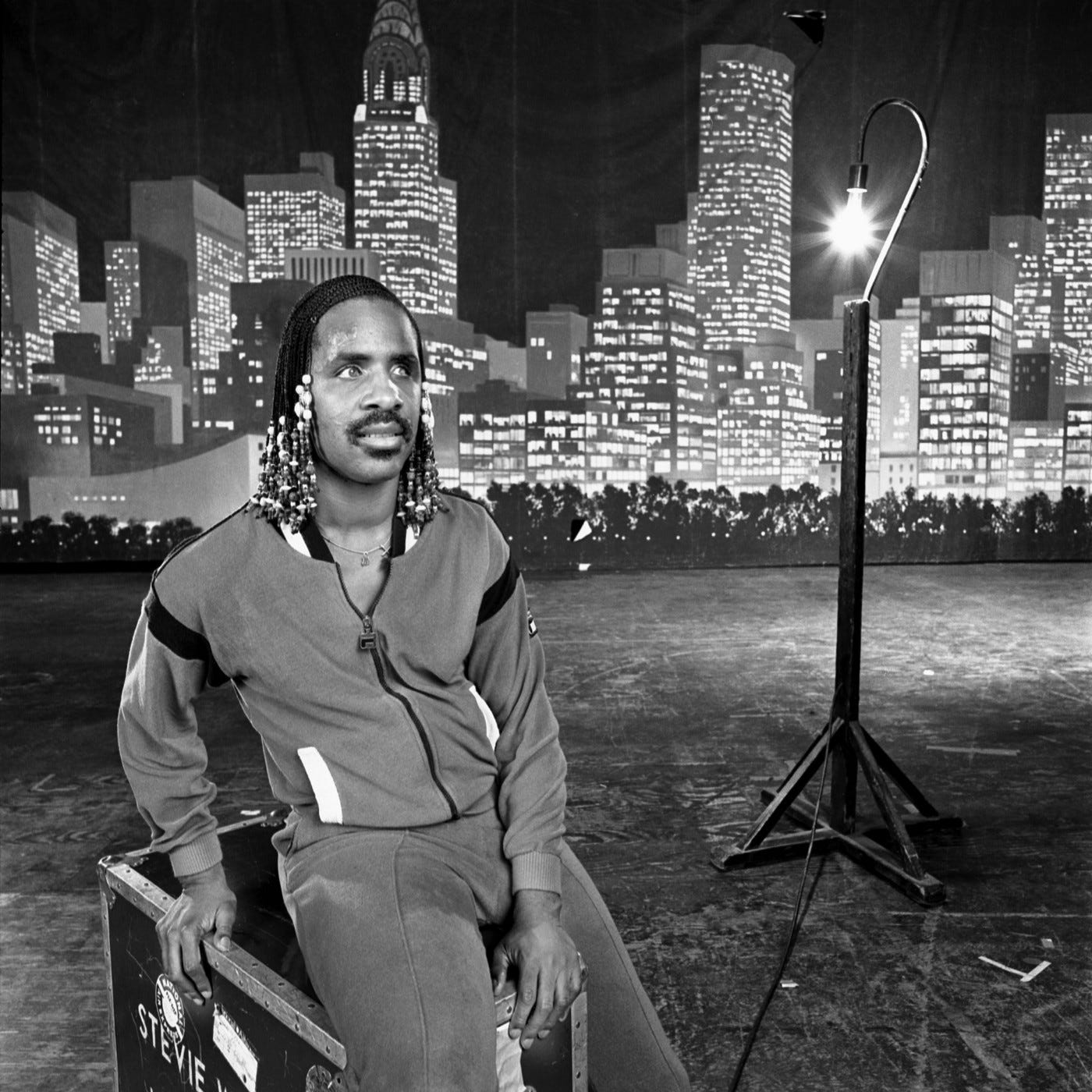

So, here we were, a year later, in LA, getting ready for a photoshoot in that humongous rehearsal hall: S.I.R. (Studio Instrument Rentals), where the biggest stars in popular music, to this day, choreograph their performances before taking the show on the road. It used to be a Columbia Pictures soundstage during Hollywood’s golden era. Directors, from Capra to Kubrick, shot scenes there for movies like It’s a Wonderful Life, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, From Here to Eternity, and Dr. Strangelove. For me, working with a musical mastermind like Stevie Wonder notwithstanding, it was a thrill to be in the very spot where actors like Clark Gable, James Stewart, Bette Davis, Barbara Stanwyck, and Burt Lancaster spoke their lines to the camera.

When I shoot a portrait, I try to include something unexpected; not necessarily controversial but something that makes it both the subject’s and my own. Because Stevie Wonder was always seen wearing dark glasses in public and in pictures, I figured I’d ask him to pose without them. Why not? I’d seen him often enough in private, casually that way. He didn’t give the idea a second thought. But I had something additional in mind.

By serendipity, another performer left a painted curtain, a backdrop, hanging in the rehearsal hall depicting a Manhattan skyline. It reminded me of a lyric from the tune “Living for the City” on Innervisions:

Wow! New York City, Just like I pictured it, Skyscrapers and everything.

Bingo, that was it! Artificiality worked in its favor, graphically. And with the obvious absence of a blind man’s dark glasses, I hoped to evoke the spirit of Steve’s “innervision” or what he wanted his audience to hear in his lyrics, further into the song: the disillusionment of a black man enduring a brutal police arrest. But just as we got down to business, I realized we had an issue. I had to explain candidly — awkwardly — how I’d have to wait short intervals between each shot, before tripping the shutter, because, well, there was no other way to say it: his eyes didn’t always coordinate the way they were expected to, in a sighted person’s world, looking in the same direction. Never mind taking my own eye away from the viewfinder; I had to catch each opportunity as it came along with no predictable cadence. Blind luck. He was okay with that. I also felt obliged to disclose that I was shooting high-resolution film; that the scar on his forehead, a vestige of his encounter with the truck, would clearly be visible. No pushback there either.

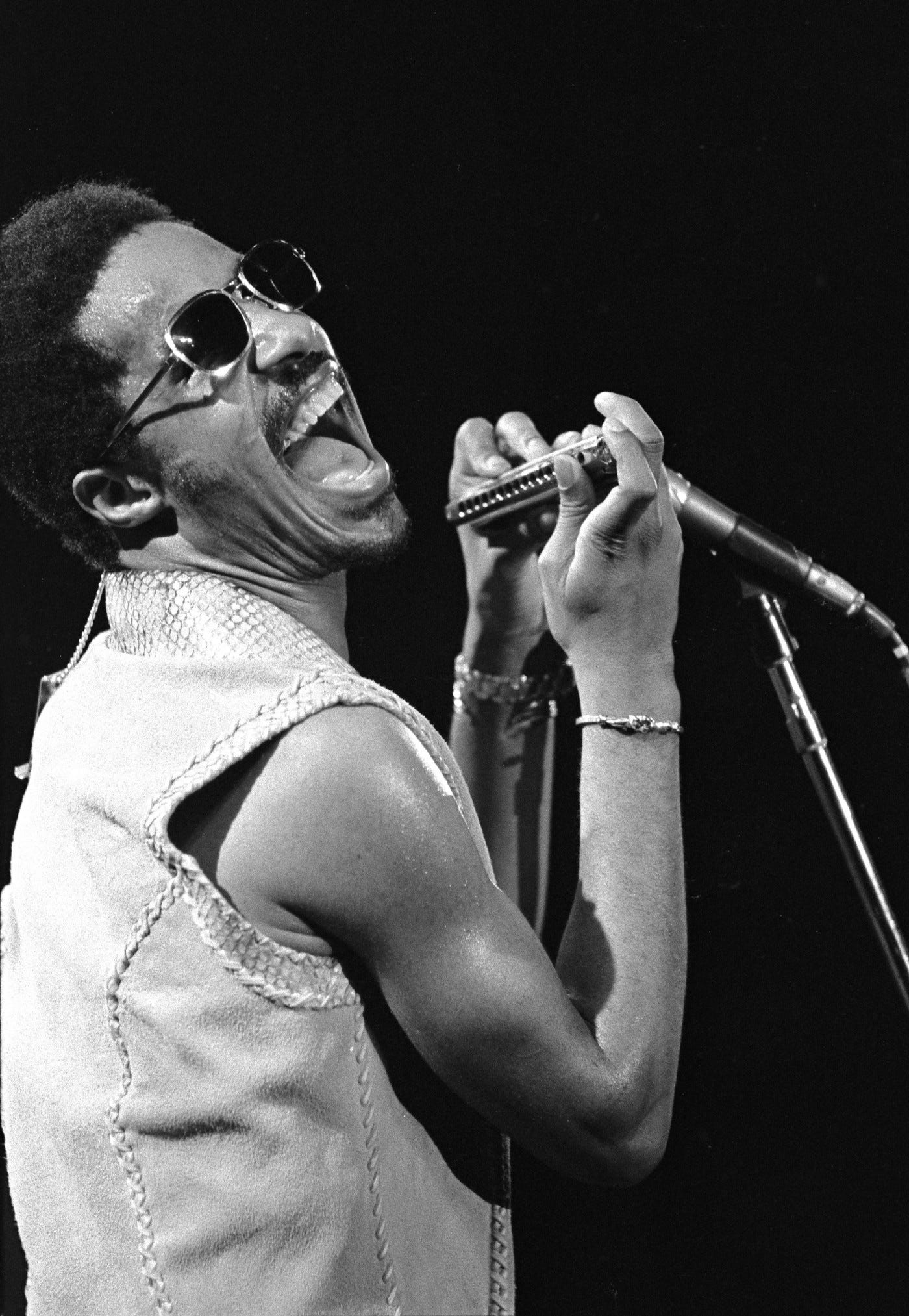

Like I said, this wasn’t our first photoshoot. Early on, I worked with Steve when he was the opening act for the Rolling Stones on their 1972 American tour. He’d be in the middle of a song, just killing it on “Superstition” for instance, while the audience, many of them, were still looking for their seats. But opening for the Stones went a long way toward introducing Stevie Wonder to a wider, if not whiter, rock ’n’ roll audience, reaching beyond R&B fans and those who enjoyed middle-of-the-road tunes like “My Cherie Amour.” And no more “Little Stevie Wonder” with his bongos and harmonica after that.

One night, during a performance with the Stones at the LA Forum, Steve, whom I must have told where I would be hiding (I liked to shoot pictures from behind an amplifier, onstage) got up from his keyboard and pulled me out by my arm — Oh, look what I found: a photographer! — to clown around, dancing in front of 18,000 people! He was an endearing goofball. But that wasn’t the only adventure I had on that tour. Another night, my legs gave out, cramped from running hundreds of feet up and down the steep stairs in the arena, lugging thirty pounds of gear to get different camera angles during Steve’s set. I collapsed just as fans in the nose-bleed seats, in anticipation of the Stones’ coming onstage, decided, as a mob, to invade the ground floor. I was trapped, drowning in the vortex of a singleminded multitude emptying like water down the drain of an arena-size bathtub. Two security guards whisked me backstage, using a fireman’s carry, where I was laid down on a bench in what was ordinarily an NBA locker room, now a dressing room occupied by a British rock ’n’ roll band. The five of them were just walking out to go onstage. I blurted out, “Break a leg!” Mick Jagger, wearing a powder blue, silver-spangled jumpsuit, unzipped down to his navel, shot me a peace sign, and Keith Richards rasped, “It looks like you already broke yours, mate.”

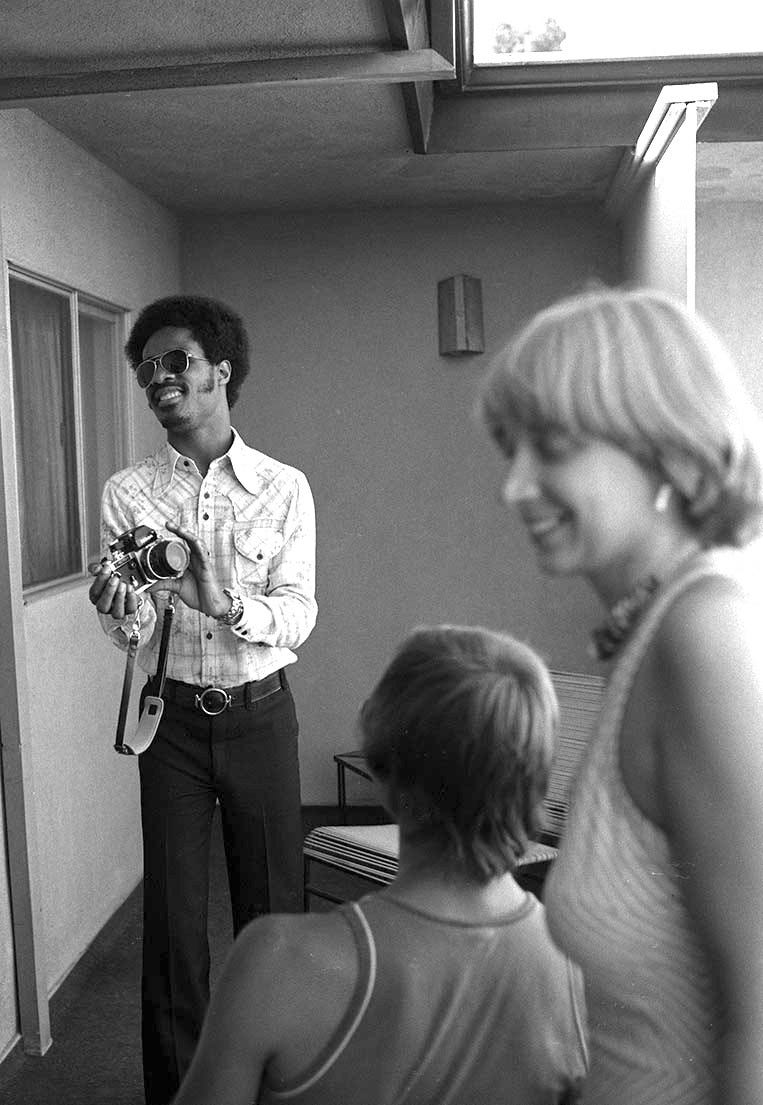

I didn’t see Steve for a while after the Rolling Stones tour or during his convalescence. But the next time we met, a few months before our portrait shoot at S.I.R., something remarkable happened. Notice the astonished look on the face of the young photographer — 22-year-old me — winding film through my Nikkormat as I step into the frame of an off-kilter photograph. It’s 1974, summertime. The scene is set on the balcony of a motel on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood.

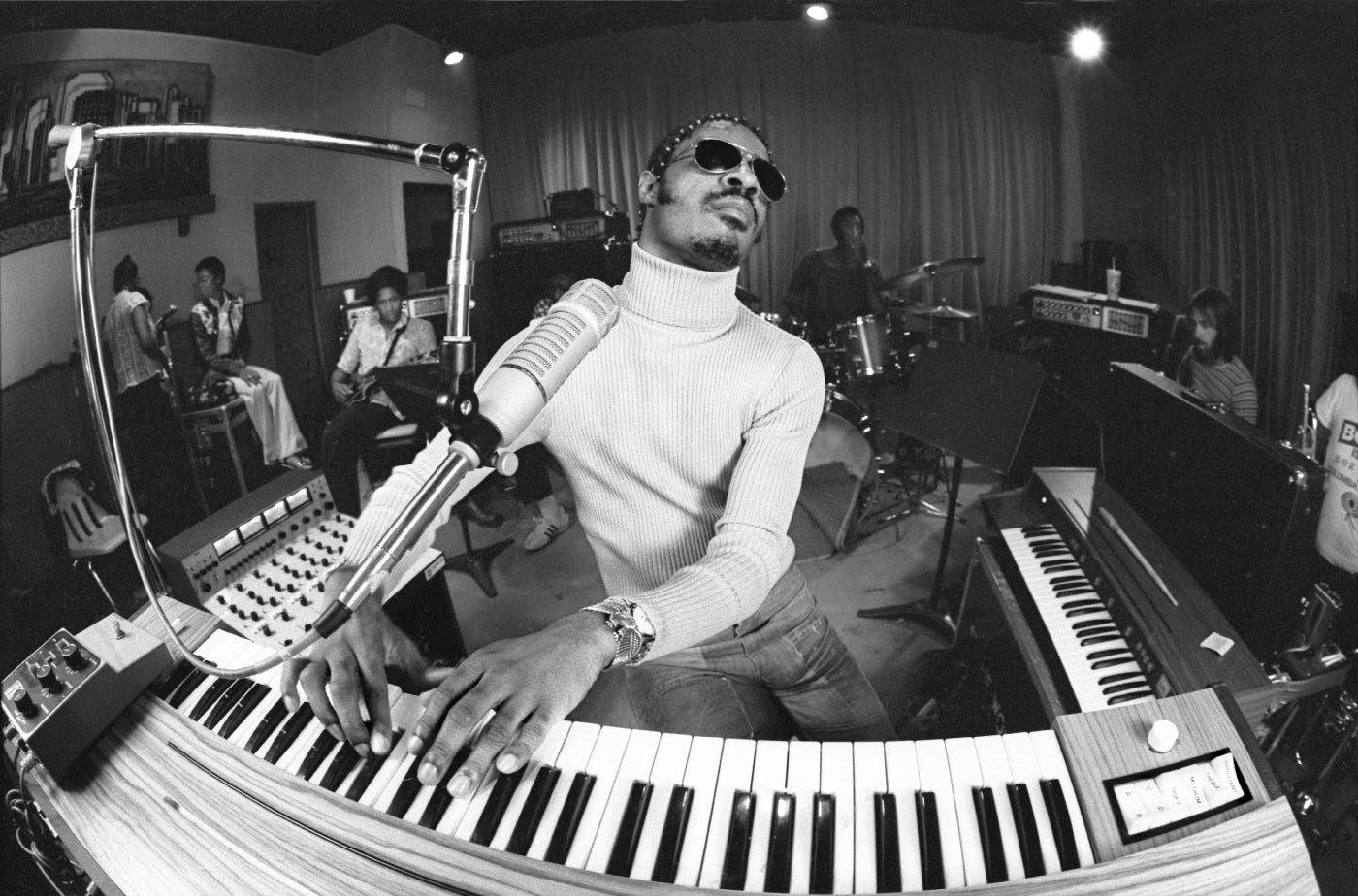

As you can see, in the next photo, another photographer is shooting the couple in the picture with me in it. He and I are situated directly across from each other, with the man and woman in the middle. I captured that opposing picture just a nanosecond later — a quickdraw. Shooting from the hip I got him before he could lower the camera hiding his face.

Then I shot another couple of frames to make sure everyone recognized the man who surreptitiously expropriated my other camera; took it right out of my camera bag when I wasn’t looking. Well, I guess you could say he wasn’t looking either.

I was on assignment for the pioneering rock ’n’ roll magazine Crawdaddy. It was Steve’s first cover and interview since the accident. His interviewers were the couple depicted in his photograph, the songwriting duo from the band Orleans who wrote and recorded hits including “Dance with Me” and “Still the One”. They were John Hall and his, then, wife Johanna. (John Hall later became a congressman from New York’s 19th district.)

Steve had fun boasting that he could see 20/20 in the dark, but that you wouldn’t want him performing surgery. He insisted he could do pretty much anything a sighted person can do, including use a camera. To prove his point, and before I could say Alfred Eisenstadt, he triangulated his savvy senses on my camera bag, lurched over, grabbed a Nikon, and proceeded to do my job. He knew where the viewfinder was and held it up to his face like he was looking through it. He pointed the lens at his subjects. This was more than a decade before auto-focus. Go figure! The whole episode was over in the wink of a lens. And I can boast that I was photographed by Stevie Wonder.

This story ends with a birthday party: Steve’s 25th. Winding down after a long day’s recording session for his next album, Fulfillingness’ First Finale, Steve’s brother told me he had arranged a surprise dinner. The producer, engineers, sidemen, friends . . . all had sneaked out of the studio, one by one, unheard, to reconvene at a Moroccan restaurant called Dar Maghreb. Only his brother and I remained with Steve, who was noodling around on the keyboard while I took pictures when he got suspicious about how quiet it had become; just camera clicks and piano licks to be heard. His brother mumbled some excuse about union overtime for the musicians and engineers and how Steve was too obsessed with work to notice that everyone had split. He said that he, too, had some business to wrap up elsewhere (off to the restaurant, actually, to let everyone know we were on our way), and asked Steve if it would be okay for me to give him a ride home. No problem. The three of us locked up, and Steve held onto my elbow as we walked toward my car in the Westlake Recording Studio parking lot.

I felt pretty smug driving Stevie Wonder around in the front seat of my car for all the world to see. He was rocking out to the radio, playing air piano on my dashboard — doing that Stevie Wonder thing he does, head swinging to and fro. He wanted me to know, by the way, that he, too, could drive a car, and I should let him next time, back in the parking lot.

I told Steve I had to make a quick stop on the way home, to drop off a package. I fibbed. He still didn’t know he was the package. When we arrived in front of Dar Mahgreb — he had no idea where we were, of course — I said, “If I leave you in the car you might steal it, so come inside for a minute to meet a friend of mine. She’s a big fan.” He laughed. I promised, in return for the favor, to make sure his pictures were in focus from now on. He laughed again. I left the car with a valet (shushing him) and guided Steve into the restaurant.

Leaving the seedy side of Sunset Boulevard behind, we entered a grandiose façade through twenty-foot tall gilded doors into a courtyard that looked like the Alhambra of Granada in all its Moorish splendor: bubbling fountain, filigreed walls, colorfully tiled floors, Berber carpets, towering arches, all surrounded by a colonnade. It was a One Thousand and One [Arabian] Nights architectural fantasy. I wish Steve could have seen it. Alas, I didn’t have Aladdin’s lamp. But he could already smell the roasted meats and cinnamon. He could hear the exotic sounds of the dumbek, the oud, and the ney accompanied by cymbals jangling on the fingertips of busty belly dancers. The jig was up. HAPPY BIRTHDAY! came the rousing cry from a dozen or so of Steve’s friends and family. After our waiter performed a traditional hand washing ceremony, we sat on the pillowed floor to enjoy a traditional Moroccan feast.

I asked Steve, “Have you ever seen a belly dancer?”

“No,” he said.

“Well,” I said, “you see with your hands, right?”

“Yeah,” he said.

“Well,” I said, “watch this.” With a wink and a nod from the dancer, I held Steve’s wrist and guided the palm of his hand onto her gyrating breadbasket.