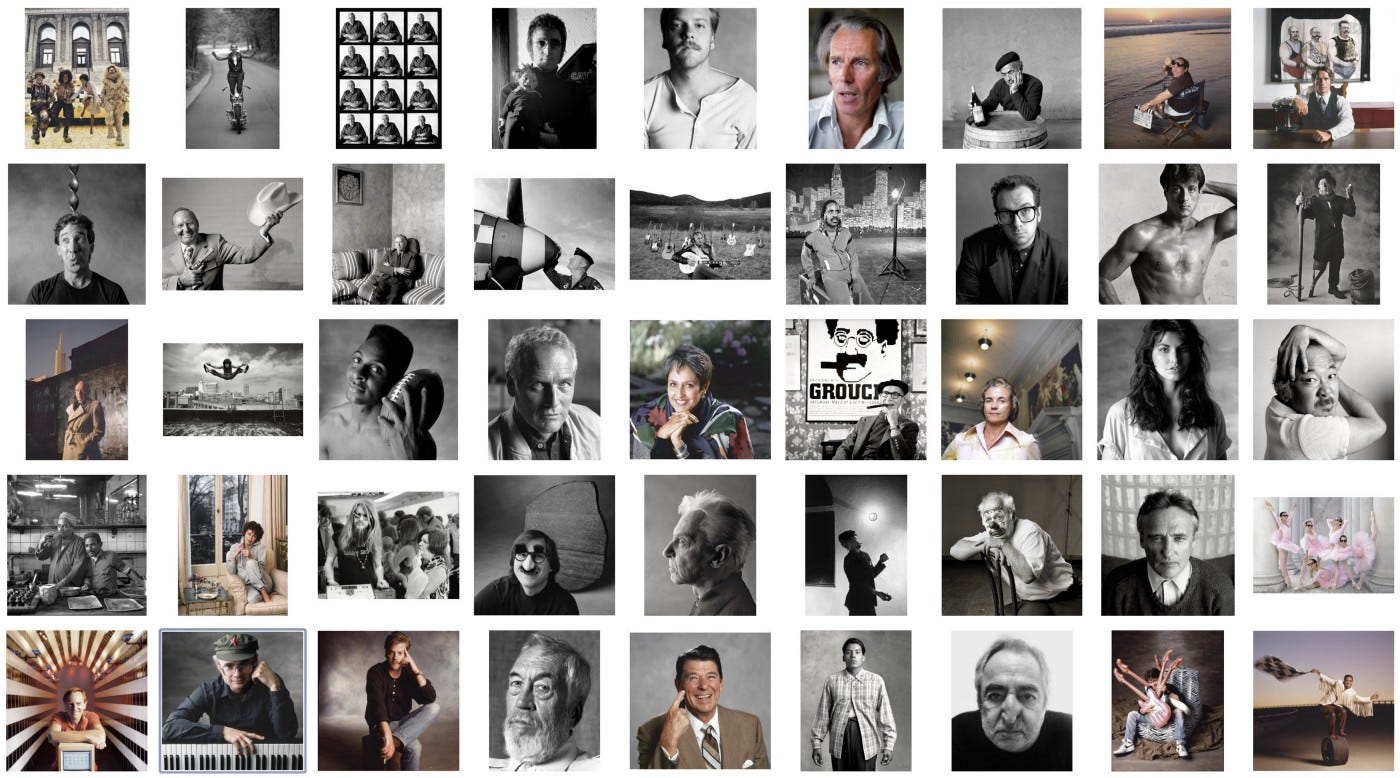

We don’t load cameras much anymore, but we still aim them and shoot pictures. With that in mind I get a bang out of describing my irrepressible pursuit of portraits as a predatory sport, hunting big game: the famous and the simply fascinating. I try to get close enough for a good clean shot — close as in rapport, not just proximity — to avoid inflicting gratuitous wounds.

For me, the memorialization of an encounter with an extraordinary human being — in one shot, so to speak — epitomizes the hunt. When it goes well, when I’m proud enough of a portrait to add it to my collection, it’s because the subject allowed me to reveal something personal — and captivating in the manner of a graphic design or composition. Predatory? I bag my quarry by looking through a lens, not down the barrel of a gun. But I still hang their heads on a wall to admire like trophies.

Despite one’s best preparations, any random photoshoot can go sideways; and, like a MacGyver episode, it becomes necessary to solve a cascade of unexpected challenges involving lenses, lights, cameras, props, wardrobe, the location, weather, deadlines… the subject’s temperament. It doesn’t always work out. Sometimes, the big one gets away.

Not every sitter is famous, but I enjoy the privilege of rubbing shoulders with movers and shakers; sometimes exchanging ideas or opinions if only for an instant of egalitarian conceit. The reward is sublime, like an unending series of masters and Ph.D. lessons about, well, just about everything.

Ultimately, my relationship with each individual I photograph is the photograph. Once in a while, a longer friendship ensues. But in every instance my subjects and I are left with what we each saw and felt in the moment, looking at each other through a lens. But the camera, on my side of the lens, is a surrogate for you, the viewer, who can stare back at an exquisitely printed portrait for as long as you wish, with no compulsion to look away.

Today, everyone has a camera. We all take pictures. We’ve all had our picture taken, often with family and friends. We’ve all got our selfie faces now, too. But the experience of being portrayed can hardly be taken for granted. It is an act of total engagement, often executed by a total stranger.

Few of us have ever been invited to sit for a punctilious photographer, isolated in a forest of light stands, cables, booms, flags, cookies, umbrellas, and other arcane paraphernalia, flinching at the loud POP! and bright flash of electronic strobes while production stylists, editors, and photo assistants hover about. Even if the experience is as simple as facing a photographer with only a camera on a tripod between you, it’s unnerving to be stared at through a lens. It’s uncomfortable taking direction, being manipulated into a pose. Regardless, a first-rate portrait is always contrived — but in the best sense of the word. It is a collaborative effort executed with deliberation and care. At worst it’s a snapshot.

I don’t capture anyone’s likeness surreptitiously; my subjects participate knowingly. Sure, I take advantage of spontaneity. But a portrait cannot be described as “candid” just for being fleet or unrehearsed. The idea of a candid portrait is an oxymoron. One has to be prepared for every unexpected mannerism or expression. However, luck is incidental to the conceptual rigor that goes into the creation of a telling portrait.

Imagine the headshot of a wizened old man in some far-flung locale (wearing a turban, probably) or the typical “pretty girl in native costume.” Despite being sharply focused, well exposed, and adequately composed, those kinds of pictures are souvenirs made on the fly by camera enthusiasts and tourists.

Photojournalists, I concede, will include stereotyped depictions in their reportage, but only as grace notes to compliment a larger group of pictures that, when well edited and shown together, tell a broader story. But, taken individually, do such photographs have the inherent characteristics of a portrait? Not in my opinion. A portrait must be more than an agreeable likeness. To be considered a success, it will concisely dramatize one aspect or another of its subject’s persona and be able to stand on its own as a work of art.

Whether shot with an iPhone or a $47,000 digital Hasselblad . . . or an oatmeal box with a pinhole and a piece of film Scotch-taped inside, a portrait is the result of a photographer’s interaction with a sitter. It is rarely a one-sided affair because, to one degree or another, it reflects the sitter’s intellectual participation as much as the obvious fact of being on camera. It should also be self-evident why a portrait was made, certainly not to recreate a cliché. In the hands of an artist, even an iPhone or an oatmeal box is a fine tool for making portraits. Only the result counts, not the kind of camera used to create it.

Regrettably, the word portrait has been commercially appropriated. To some people it simply means the vertical framing of a photograph. But portraits are also composed horizontally, sometimes within a square. Portraiture is an art form, not a format.

Although a portrait should not be expected to flatter, there is no reason why it cannot. Many great examples do. It’s just not a prerequisite. However, it’s reasonable to say that a portrait should not be deliberately insulting. Regardless, the parties on opposite sides of a camera don’t always agree on what’s good or bad. Generalizations can be made, too. For instance, I have no compunctions about showing every whisker and pore on a man’s face. But would I dare show such sharp detail on a woman’s face? There will be exceptions, of course. Or what about makeup? Even with a male subject, makeup may be a practical consideration for, say, a magazine cover or commercial illustration, if not for art’s sake. There are no rules governing style or technique. If there were, artists would surely find reasons to break them.

Portraitists, whether they rely on film, pixels, pencils, or paint, are storytellers. Those who use a camera are concise storytellers indeed, working in a medium with only two dimensions (unlike sculptors) and only one frame (unlike moviemakers). Photographers have less leeway than writers (in particular biographers) who can exploit their readers’ boundless imaginations. One also hopes to make a portrait during an important episode in the subject’s personal life or career because it adds to a good story; and the moment itself is preserved in historical context.

Creating art makes us human. Looking at humans as the subjects of art comes full circle with portraiture. When photons bounce off living beings, yanked through the barrel of a lens by an occult force called “the mind’s eye” to converge at a focal point on a light-sensitive substrate inside a dark box, two parties on either side of this contraption, a camera, are committed to telling a story for one endlessly enduring moment. That’s portraiture: the still life of a human being. It’s magic.